The Truth Behind the “Golden Penguin” Discovery

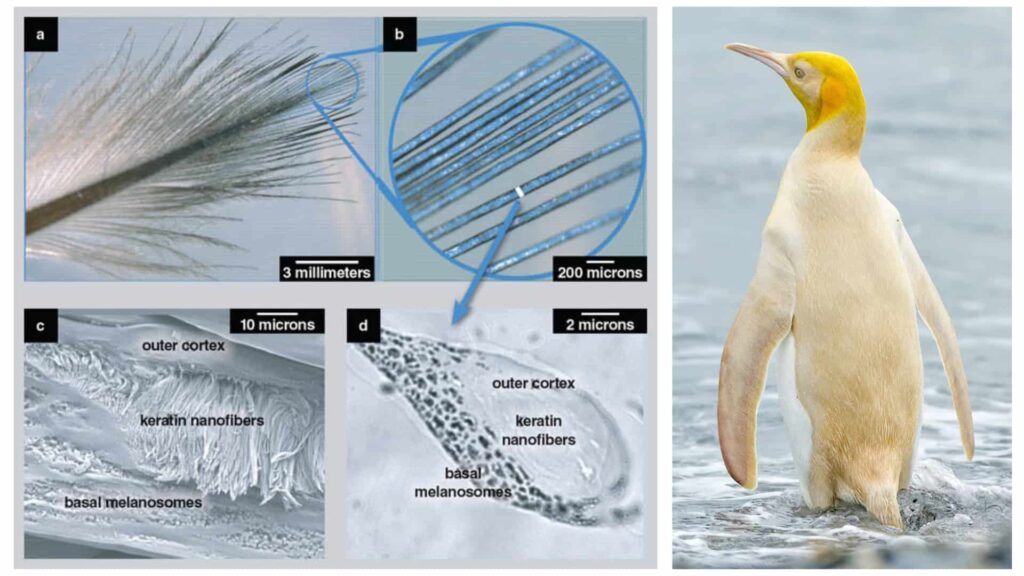

You might have seen the striking photo of a yellow-feathered bird among thousands of tuxedo-clad penguins. That bird wasn’t CGI. It was a real King Penguin with an unusual colouration. Let’s walk through what we know, what we don’t, and why it matters.

What happened

- In December 2019 a wildlife photographer named Yves Adams landed on a beach of South Georgia Island in the South Atlantic. He counted around 120,000 king penguins in one colony. (Live Science)

- Among them he noticed a bird whose feathers were pale cream or yellowish instead of the usual black-and-white. He described it as “the only yellow one there.” (Live Science)

- Later that image circulated widely, sparking interest under labels like “golden penguin”, “yellow penguin”, or “rare penguin discovery”.

Why this matters

- The sighting challenges our assumptions about what a typical penguin looks like and shows how genetics and environment can combine to produce unexpected variation.

- It reminds us that even species we think we “know well” still hold surprises.

- It prompts questions about how mutations affect survival, reproduction, and conservation.

How a Genetic Mutation Turned a Penguin Yellow

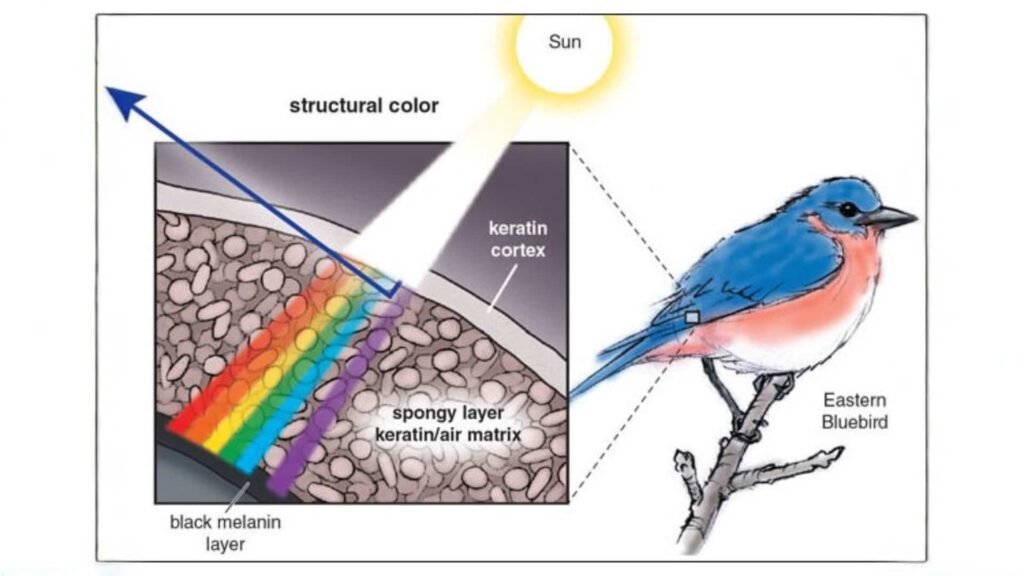

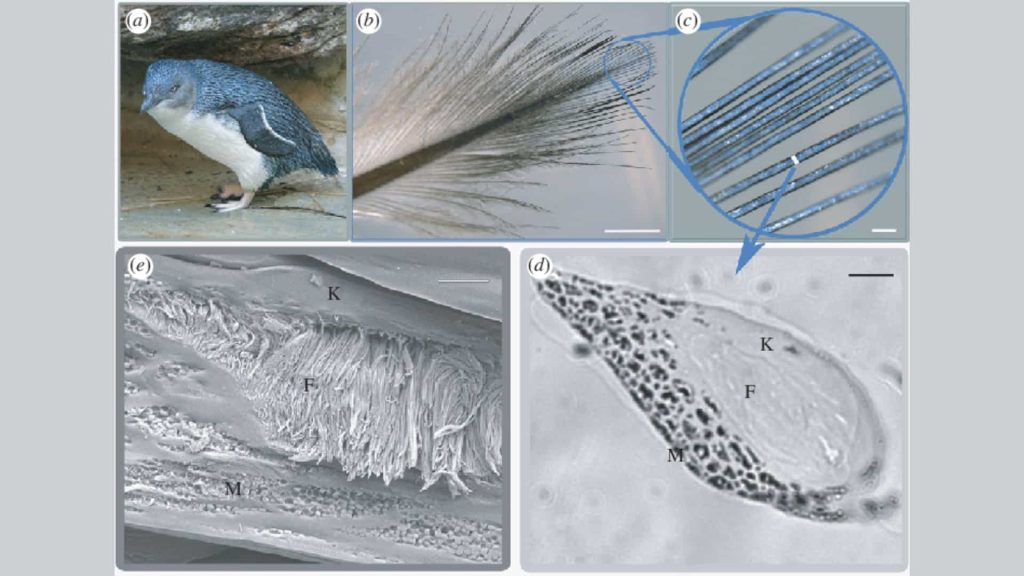

What pigment normally does

- In most king penguins the black areas are dark because of melanin. (sora.unm.edu)

- The yellow/orange patches (especially around the neck) are from different pigments (carotenoids or similar) rather than the melanin that gives black/grey/brown colour. (National Geographic)

What likely happened in this case

- The “yellow penguin” likely lost or failed to deposit normal amounts of melanin in its feathers, leaving the yellow-based pigments visible and the usual dark feathers pale or cream. Several sources call this condition leucism. (Live Science)

- Some scientists disagree on whether it’s purely leucism or more extreme (closer to albinism) because the bird appears to lack melanin almost entirely. (IFLScience)

What a genetic mutation means

- Mutations affecting pigment genes can reduce melanin production or the ability to incorporate pigment into feathers.

- These mutations are rare. For instance, an earlier study of king penguins recorded only 19 cases of various colour aberrations over decades. (sora.unm.edu)

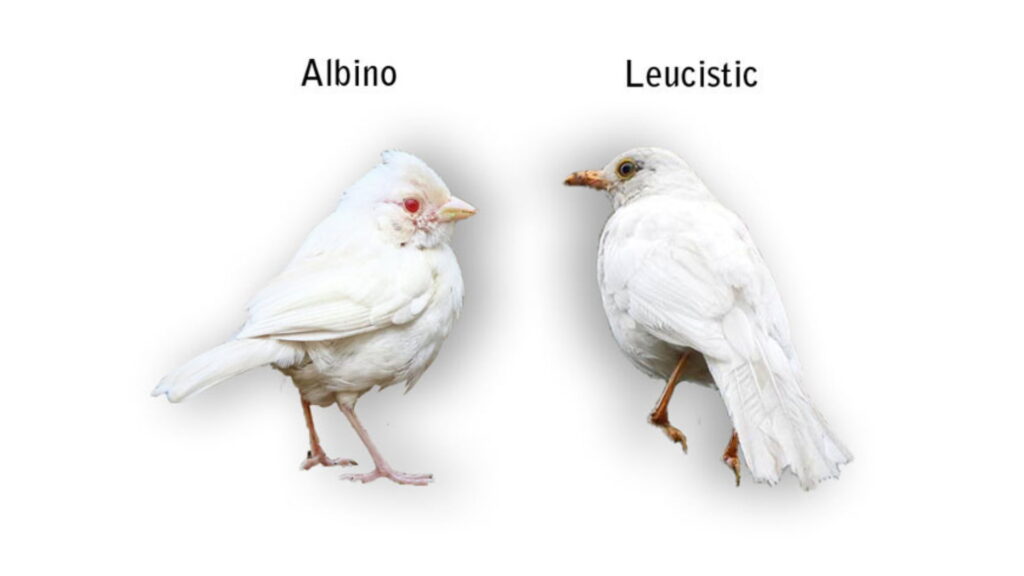

Leucism vs. Albinism: What’s the Difference?

| Term | What it means | In the penguin case |

|---|---|---|

| Albinism | No melanin produced at all; results in white feathers, pink eyes/skin. | Some scientists suggest the yellow penguin might approach this because of very low melanin. (IFLScience) |

| Leucism | Partial loss of pigment or pigment-cell malfunction; can retain some colour and normal eye colour. | Many sources label the yellow penguin leucistic. (Live Science) |

In short: If the bird retains some pigmentation (especially in eyes) and some non-melanin pigments show through, it’s leucism. If it lacks almost all pigment, it may be albinism or a near form of it.

The Rare South Atlantic Penguin That Stunned Scientists

The species

- The bird belonged to the species king penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus). (Wikipedia)

- King penguins are the second largest penguin species. They stand around 70-100 cm tall and weigh roughly 10-16 kg (depending on season and feeding status). (Science Times)

- They breed on sub-Antarctic islands like South Georgia, with huge colonies of tens or hundreds of thousands of birds. (BioMed Central)

The location

- South Georgia Island is remote, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, roughly 1,200 miles (≈2,000 km) east of South America’s southern tip. (National Geographic)

- The specific beach where the yellow penguin was spotted among ~120,000 normal ones was reportedly “Salisbury Plains” on South Georgia. (National Geographic)

Why it surprised scientists

- Because colour aberrations at this scale are extremely rare for penguins. Only a handful of documented cases exist. (sora.unm.edu)

- Because the contrast was so stark: one pale bird among a sea of black-and-white.

- Because it opens questions: how does this affect mating, survival, camouflage, and peer interactions?

How Common Are Colour Mutations in Wild Animals?

Mutation incidence

- Colour mutations (albinism, leucism, melanism) happen across many species, but are rare. For example, a study found ~19 colour aberration cases in a king penguin colony spanning decades. (sora.unm.edu)

- On South Georgia, a study found leucistic fur-seal pups with a prevalence between ~1 in 400 to ~1 in 1,500. (National Geographic)

Why mutations don’t dominate

- Many colour aberrations may reduce survival: increased visibility to predators, reduced camouflage, altered social interactions. (National Geographic)

- If a mutation affects mate attraction (especially in species that use beak/feather colour as a signal), then the chance it passes on is low. (National Geographic)

But sometimes they persist

- Some aberrant-coloured animals survive well. In the National Geographic article penguins with mutations seemed accepted in their colony and appeared behaviourally normal. (National Geographic)

So while we might call the “yellow penguin” a freak occurrence, the event falls within known possibilities—just very uncommon.

The Role of Pigments in Penguin Feathers

What colours do

- Black / dark feathers: absorb sunlight, provide warmth, and may assist camouflage from predators below. Melanin plays a key role. (sora.unm.edu)

- White / light under-belly: helps reduce visibility to predators below (counter-shading).

- Yellow / orange patches: in many penguins, these colours serve as mate attraction signals or species-recognition features. For example, king penguins have bright yellow patches on their necks naturally. (National Geographic)

What happens when pigment goes wrong

- If melanin is absent or weak, feathers that should be black become pale, weakening camouflage or heat absorption.

- If the yellow patches remain unaffected (because they use different pigment pathways), you get odd combinations (e.g., pale body plus yellow crest). That seems to be what happened in the yellow penguin case. (National Geographic)

The “golden” effect

- Because the dark pigment faded, the yellow patches stood out far more. That is why the term “golden penguin” caught on.

- The standing-out may influence peer behaviour, mate choice, and visibility to predators or prey.

Why South Georgia Island Is a Haven for Unique Wildlife

Location and environment

- South Georgia is a remote island in the sub-Antarctic, mostly free of human habitation and large land predators, which allows large colonies of seabirds and marine mammals. (National Geographic)

- Its isolation means mutations may be more easily observed (fewer disturbances) and less likely to be immediately weeded out by human interaction.

High density of wildlife

- The sheer number of king penguins and other species means higher chances of observing rare events, like colour mutations. When you have 120,000+ individuals in a colony, even a 1-in-100,000 chance becomes visible.

- The island’s beaches often host mixed gatherings of penguins, seals, and other marine fauna, making it a live-field for wildlife photography and research.

Genetic “founder effects” and variation

- Some research suggests colonies on remote islands like South Georgia have unique genetic signatures even among the same species elsewhere. For example, king penguins from Crozet, Macquarie, and South Georgia show low genetic differentiation, but subtle differences exist. (BioMed Central)

- The island environment may support the survival of unusual variants long enough to be photographed.

How One Photo Changed What We Know About Penguins

From single sighting to scientific interest

- The photograph by Yves Adams brought widespread awareness of how pigment-mutations occur even in well-studied species like the king penguin.

- It sparked dialogue about the difference between leucism and albinism, prompted studies and reports in outlets like LiveScience, National Geographic, IFLScience. (Live Science)

Implications for research

- It reminds scientists to look out for anomalies in large populations and record them, because what appears “normal” may hide surprises.

- It invites questions: Do such individuals breed? Do they survive to adulthood? How do they compare in fitness to normal-coloured peers? Few follow-up studies exist—so there’s room for new research.

- It becomes a teaching moment for genetics, pigment biology, and wildlife conservation.

Public and social impact

- It captured public imagination. “Gold penguin” memes, Instagram posts, nature-photography features.

- It brings wildlife science to a wider audience, which helps conservation awareness.

The Science Behind Animal Colour Variations

Types of variation

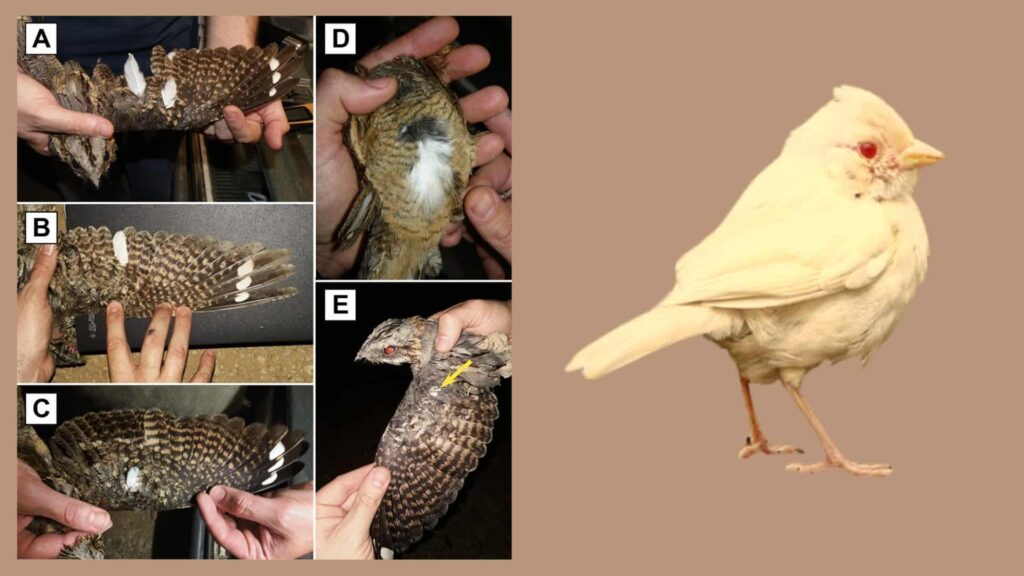

- Melanism: excess melanin – animals appear darker than usual (e.g., “all-black” penguins have been recorded) (The Daily Herald)

- Albinism: absence of melanin – animals appear white/pale, with pink or red eyes

- Leucism: partial loss of pigment – feathers/fur may be pale or patchy, eye colour usually normal

Mechanisms

- Mutations can affect pigment production, pigment transport, pigment deposition in feathers/skin.

- Environmental factors (diet, health, injury) can also cause unusual colouration, though genetic causes are more permanent and consistent. (National Geographic)

Survival and evolution

- Colour-mutant animals may face disadvantages (visibility, heat regulation, signalling to mates).

- But sometimes they survive well enough; the key is whether the trait affects survival or reproduction. In some cases, mutant individuals breed normally. (National Geographic)

How Social Media Turned a Rare Penguin Into a Global Sensation

- The image of the “golden penguin” spread through Instagram, Reddit, news sites, and blogs.

- The catchy story (“yellow penguin among 120,000 black-and-white ones”) made it shareable.

- It became a symbol of wildlife wonder, genetic oddity, and unexpected nature.

- The popularity helps draw attention to colonies, remote islands like South Georgia, and to the study of wildlife mutations.

- It also raises a caveat: when something goes viral, accuracy can get blurred. Words like “golden penguin” or “new species” may mislead. Always check the science.

Other Rare Animal Colour Variants You’ve Probably Never Seen

Here are some quick examples:

- A melanistic king penguin (almost entirely black) was spotted on South Georgia. (The Daily Herald)

- Leucistic fur-seal pups on South Georgia have been recorded at a ratio of ~1 in 400-1,500. (National Geographic)

- Albino or leucistic deer, birds, and marine animals occur in many places—each case invites questions of survival, breed-success, and adaptation.

These cases remind you that “rare” doesn’t mean “impossible” — and nature’s full of variation if you look closely.

FAQ

Q: Is the “yellow penguin” a new species?

No. It’s the same species as the typical king penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus). The difference lies in pigment mutation, not a separate species. (National Geographic)

Q: How many golden or yellow penguins exist?

We don’t know an exact number. Only a few documented cases exist. One famous individual among ~120,000 penguins was recorded in 2019. (Live Science)

Q: Could this mutation be inherited and spread?

Possibly, but wild data is limited. Colour aberrations may reduce chances of mating or survival. For example, varying signals (colour patches) matter in mate choice. (National Geographic)

Q: Does this mutation harm the penguin?

Not necessarily. Some observations suggest aberrant-coloured individuals act normally, feed normally, and integrate into colonies. But the full life-history data for this particular yellow penguin is lacking. (National Geographic)

Conclusion

The appearance of a “golden penguin” on South Georgia Island offers a window into the unpredictable side of nature. It shows how a species we know well can still surprise us. The bird is not a new species, though it reminds us of other Newly Discovered Species, each revealing how evolution still unfolds before our eyes. It’s a king penguin altered by pigment mutation—likely leucism but possibly closer to albinism.

Its story demonstrates how genetics, pigment biology, ecology, and chance converge. For you as a reader (or writer), it’s a reminder: look to the margins, because that’s often where nature shows creativity.

Author: Mubashir Razzaq

Nature Writer and Research Contributor